In search of Sir James Taylor

The youngest and the only RBI Governor to die in office, Taylor is the first true central banker of India spending almost his entire career in the cause of Indian central banking for about two decades

As an Economics student for my undergraduate degree, I opted for Banking Theory and Systems as an optional paper. My college was among the few in my university that offered the paper. The prescribed readings included Richard Sayers’s Modern Banking, former South African Reserve Bank Governor MH de Kock’s Central Banking, and Beckhart’s massive volume on Banking Systems. Sayers would write the volume on the History of the Bank of England from 1891 to 1944 that also covered the establishment of the Reserve Bank of India. The Report of the Banking Commission headed by RG Saraiya (more on him in a future post) provided a different India touch lacking in Beckhart. Beckhart contained chapters on banking in other countries from which, apart from India, USA, UK, France, Germany, Japan, the USSR, and PR of China, were among the required readings.

Beckhart’s was an edited volume, the chapter on India written by BK Madan, one of the Bank’s early outstanding Deputy Governors and among the first from the Economist stream. By the time Beckhart became my textbook in 1978, it was already in its fourth and last edition of 1970. The chapters were updated with an addendum, most of which was written by officers from the Reserve Bank of India’s Economic Department. This Indian edition was published by The Times of India Press. Mr. M Narasimham, then a Deputy Adviser in the Economic Department, wrote the addendum for India.

In 1978, the book was already out of print. I had to tap my father's economics teacher and later (not-so-happy) bridge partner, Prof VR Pillai, for a personal copy, duly returned. May God bless his soul. An LSE alum, Prof VR Pillai established the Economics Department at the University College in the early 1930s. By then, Narasimham had become Governor and gone. The book was already on its last leg, with global developments including in India happening too fast. Beckhart soon became outdated. So did Sayers and Saraiya’s Banking Commission Report—and de Kock, too, though much later.

Beckhart and de Kock would instil in me a lasting curiosity about central banks, central bankers, and central banking. Information on the workings of some central banks, say, the Bank of Russia and the People’s Bank of China, is still scarce. While studying the Reserve Bank of India’s history, one is handicapped by the lack of information on the people who headed it over the years, their backgrounds, personalities, successes and shortfalls.

In the first four decades of the Reserve Bank’s history, CD Deshmukh was the only Governor who wrote his autobiography. Dhanvanthi Rama Rau was the only spouse of a Governor who wrote hers. But, Lady Rama Rau had an active life independent of her husband, and she hardly touched upon the Bank or even the Governor’s residence in her book. Durgabai Deshmukh also wrote her autobiography, but she married Deshmukh only after he left the Bank. Thus, information on the early Governors, even celebrated ones such as Benegal Rama Rau and Lakshmi Kant Jha, is hard to obtain.

In the case of Sir Osborne Smith, the Bank’s first Governor, the gap was covered to a great extent in an exceptionally well-researched and brilliantly articulated essay by Anand Chandavarkar (EPW, August 2000). Chandavarkar belonged to the group of economists who joined the Bank in the late 40s and 50s, undoubtedly the golden era of the Bank’s Economic Department. One of the stars of this elite group, he later moved to the International Monetary Fund. Among his many books, I would use his Central Banking in Developing Countries as one of my primary references (along with de Kock) while teaching central banking at the Reserve Bank of India’s Zonal Training Centre and Staff College.

Chandavarkar explored the life and tribulations of Governor Smith in some detail, including the long standoff with the senior among the Deputy Governors, Sir James Taylor, and the Finance Member, Sir James Grigg. While doing this, he gently reprimanded SLN Simha (a stylised abbreviation of SL Narasimha), who wrote the first volume of the Bank’s official history, for overlooking this sordid episode. Simha, then into his late 80s, rendered a relatively weak defence (EPW, May 2001).

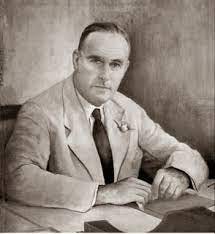

Chandavarkar later wrote on Sir Jeremy Raisman, the Finance Member who succeeded Sir James Grigg, titling his piece “Portrait of an unsung statesman extraordinaire” (EPW, July 2001). Chandavarkar seemed determined to fix these gaping holes in the Bank’s history with missionary zeal. So, it is unclear why his campaign excluded the Bank’s second Governor, Sir James Braid Taylor (some official records misspell the middle name as Baird). The reason may lie in Smith being viewed as the wounded hero, an underdog hounded out for standing up for the Bank and central bank independence. Therefore, as one of his two main adversaries, Sir James Taylor became a villain by association. Taylor’s life and achievements remained unexplored. As a result, there is hardly any information on Taylor, whether in the official History of the Reserve Bank of India for the relevant period, other historical accounts, the website of the Bank, Wikipedia or other resources in the public domain.

The complete and correct details of the ugly and prolonged standoff that marred the early days of the Bank’s history might never be uncovered. But, an examination of the life of Governor Taylor, who succeeded Smith as Governor, throws some light on the person and the events of the period. In the process, we learn more about the elusive Governor who neither left behind a memoir nor was the subject of a biography or a research paper. Some results from my search for Sir James Taylor can be accessed in the link below.

This post is part of a longer work and does not claim to be complete in many respects. You could even accuse me of holding back some interesting, though not-so-material, information for a future post. Partly, the reason is that the post is already extra long at around 15k words per my last count. It is divided into convenient sections, providing dividers and hyperlinks for smooth navigation.

I urge you to read till the end, even if you skip some less exciting sub-sections on the Reserve Bank Bill that are in the middle. At the risk of being labelled a click-baiter, I promise that plodding your way to the end could be rewarding in more ways than one. Ultimately, you might discover something compelling - or disturbing - depending on how you view it!

Note: I sincerely thank the ready, comprehensive, and unhesitating assistance from Andrew McMillan, Hon. Archivist, The Edinburgh Academy.