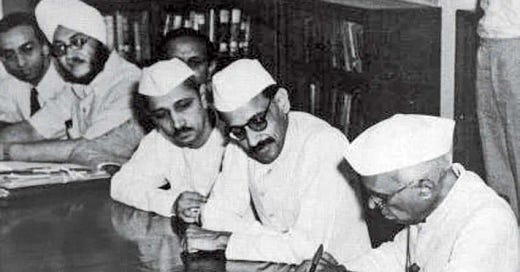

IG Patel at the Ministry

In this third part on the life and work of Dr IG Patel, we cover most of his tenure as Deputy Economic Adviser. We also revisit his academic years, some of his mentors, and a meeting with PM Nehru.

Since I wrote my last post on Dr IG Patel, there has been a change of guard at the Reserve Bank of India. Sanjay Malhotra, a civil servant, replaced another civil servant, Shaktikanta Das. In my first piece on IG, I wrote how his tenure neatly divides the history of the Reserve Bank of India into two: one before IG and the other after IG, marking the decline of the career civil servant and the rise of the economist at the helm of the central bank.

Barring two early exceptions, RN Malhotra and S Venkitaramanan, and ignoring a sole short-term incumbent, the Governors after IG have been either economists or civil servants with a doctoral degree in economics or related areas and vast experience in economics-related areas. That scenario changed with Shaktikanta Das. It is too early to say whether this is a decisive departure from the past.

If the government were to persist with a third career civil servant after Sanjay Malhotra, one could say that a third phase would have started, just as some Hindusthani musicologists write that it would require at least three generations to define a Gharana. In which case, where was the ‘fault line?’ Future historians, please note! It perhaps lies with the two Governors preceding Shaktikanta Das, who are probably guilty, along with those who egged them on, of taking the meaning of ‘central bank independence’ too literally.

The third part on Dr IG Patel can be accessed in the maroon link below:

In what follows, I discuss in a circuitous route why this third part was delayed by over three months. I begin with a tribute to an old friend from the Bank, concluding with why this post was delayed. This is more of a personal record and a tribute to an old friend, which might not interest most people, especially those not connected with the Bank.

Sahoo, my friend

Among my friends, Ashish Sahoo was one of a kind. He was rare because our worlds were quite different even though we studied at the same university department and worked at the same Bank. He was around ten years my junior, and we followed different career paths. He was in one of the research departments, and I was in the ‘general side,’ where we worked anywhere from currency vaults to inspecting large banks.

The affable Sahoo

Ours was a chance meeting. At the end of 1995, he was moving into the flat we were vacating and dropped by to see what it looked like. I quickly liked his jovial demeanour, laid-back attitude, and ability to speak almost equally with anybody, senior or junior. Taught at Xaviers College, Calcutta, by Prof Asim Dasgupta, later Finance Minister of West Bengal, and by Late Abhijit Sen and Jayati Ghosh, at JNU, I believe he remained pally with them all even years later. There could be more that I am not aware of.

At the Bank, he had no airs of making fundamental contributions to Economics, either in theory or practice. He was great for an evening chat. Even during office hours, when I needed a break, I went down from my 13th floor to his 7th of the New Central Office Building. When I left the NCOB for the Bank’s other offices, Sahoo was my go-to person to borrow some books or get some odd journal paper photocopied from the library under his Department’s control. Sometime in 1996 or 1997, I got him to copy Diamond and Dybvig’s 1983 JPE paper on deposit insurance; he told me he was impressed.

Lassie’s friend

If there was only one good reason that Sahoo became great friends, it is that he was pally with Lassie, our beige Labrador. Whenever I walked in through the door, Lassie, who sat on the sofa with her back to the door, barely lifted her snout, resting on the armrest. At best, she would raise an eyebrow and throw back a glance to confirm that the man at the door was that irresponsible guy who roams the city without caring to take her anywhere.

Whenever Sahoo made his appearance at the door and stood there waiting for Lassie’s reaction, she perked up, all alert and ears cocked up as much as a lab could. Her body would wiggle vigorously, and she would go into her routine of zoomies around the room, threatening to break anything in the way of her heavy tail’s swish. After several rounds, she would quickly go to where her leash is kept and bring it to Sahoo. They would then disappear for half an hour, Lassie coming back all refreshed. I was, of course, jealous. And I asked Sahoo one day how Lassie knew you were a bachelor. He would laugh louder than anybody else.

Finding a place to keep Lassie whenever we had to be out of the city was a tough challenge. Sahoo almost always volunteered, occasionally shifting into our house for up to two weeks.

The gourmet

Sahoo was an excellent cook, and I got a first-hand taste of it several times, including when I stayed with him for about a month. I asked, "Aren’t aristocratic Bengali bhadralok families in Calcutta known for keeping Oriya cooks?" He laughed heartily without commenting.

After I moved to Chennai, Sahoo visited the city for a two-week econometric modelling training. He called me up on the first day. The same evening, I picked him up from the hostel and took him to a now-defunct Bengali restaurant called Annapoorna in Egmore for dinner. Run by a couple in a makeshift ramshackle tenement, people ate sitting on benches. The food was as close as one could get to homemade fare in a restaurant. The prices were dhaba-cheap. Patronised mainly by Bengalis and Oriyas, Annapoorna was a well-kept secret, and people walked in and out stealthily as if they were engaged in a nefarious operation. The pungent flavour of mustard oil hung in the air.

The menu was almost exclusively nonvegetarian. But, thankfully, there was rice and roti, dal, aloo posto, shukto (mixed vegetables), and mochar ghonto (banana flower), for a vegetarian like me. But I was not spared the dirty looks reserved for vegetarians. The posto was no match for what Sahoo could dish up. But, he had a range of options in nonvegetarian fare and was at a loss for what to choose. After Sahoo placed his order, he was initially sceptical. But, as he ate, I realised he was relishing the food. He reordered some stuff. Finally, he was completely sold out on the place. Over his next 12 days in the city, he visited the restaurant ten times, he revealed with no sign of embarrassment. He tried out all that he wanted to. He also introduced the place to a few friends.

Last meeting

A few years after I moved to the Reserve Bank Staff College, sometime in 2007, Sahoo became unwell. I do not know the exact nature of his illness, but I believe some infections resulted in tuberculosis of the brain. He went a few times to the Christian Medical College, Vellore, for treatment. On his way, he broke his journey in Chennai and stayed in one of the college rooms. It fell upon me to arrange for his stay.

I contacted an acquaintance, Dr V Sitaram, who was and is still with CMC. We travelled together on a long flight to Hong Kong. He attended a three-month programme at the University of Hong Kong. I delivered a talk on operational risk at the Asia Pacific Conference of GARP. His travel was official. Mine was semi-official. Since it was a personal invitation, the Bank provided me with leave from the office. I bore the travel and other costs, except for the stay at GARP’s expense. To digress, Sitaram was a nephew of M Subramaniam, one of the most brilliant officers of the Reserve Bank I interacted with as a trainee officer. He is believed to have authored the Exchange Control Manual, which was then in vogue. Subramaniam was one of the most popular and highly regarded Managers in charge of a problematic office like Kanpur. Friends like Raghavendra Lal Das, my senior at the University, joined the Kanpur Office when Subramaniam was the Manager and held him in high regard. He was expected to rise but retired as Chief Officer of the Department of Currency Management.

I requested Dr. Sitaram to inquire about Sahoo and get back to me. He did get back but sounded a bit evasive. I understood it would be unethical for a doctor to divulge too much detail.

I met Sahoo in his room during one of his stopovers in Chennai, accompanied by his sister. As I left, he saw me off outside the hostel building and hugged me tight. He wouldn’t let go of me, so much so his sister had to step forward and release me from his grip.

A few months later, I received an email from Dr Anupam Prakash, now an Adviser in the Department, informing me that Sahoo had passed away about fifteen days earlier.

A possible posting

This long introduction to Sahoo was partly a tribute to a great friend. It was also to share what he told me one day.

Sahoo had a knack for getting to know things earlier than others, at least me, who was among the least glued in on office gossip. Some people made a career out of it. According to Sahoo, the Bank considered transferring officers from the research department to the general side and back more frequently, maybe even making it compulsory. He added that I could be among the first to move to the Economic Department. I have no idea how he got this news. And even if there was an element of truth in it, I have no idea whatever got into the minds of those who zeroed in on me.

The research and operational departments tended to work in silos for a long time. It was worse earlier, till the early 1970s when there was separate seniority in different departments. For many reasons, I counted myself among those from the ‘General Side’ who knew disproportionately more people from the research departments than most others. First, the economics department probably had the most recruits from my university department. I got to know even those many years junior through various alums meets. At least two of them studied at the Presidency College, Calcutta, where one of their Profs asked them to meet me after joining the Bank. Second, I stayed long in the Bank’s Bandra quarters, favoured by research officers. Third, I attended at least two specialised training programmes for research departments and was the only one not from these departments.

If a fourth reason is required, I spent almost a year travelling on a chartered bus used and run by research officers. It was run by a wonderful couple, Prasad and Abha, now at the IMF and World Bank. Coincidentally, Prasad’s father, R. Ananthakrishnan, was my landlord in Chennai. As a young officer posted to Chennai, I spent many evenings at the Staff College Library in the city, where I met some of them as trainees. I made several friendships on that dreary two-hour drive from Goregaon to Fort. By the way, Abha and Prasad hosted me for a lovely dinner on my only visit to Washington in 2013, and I took the liberty of asking my friend Aditya Kishwar to join in.

But would I want to move to the Economic Department? The answer was no, and I told Sahoo so. There were two reasons, which I will elaborate on in subsequent posts.

Why delay

When I started writing about IG’s time at the Ministry, I faced multiple problems. It brought back unpleasant memories of some of the most boring lectures on economic planning and econometrics, which made me a lifelong economics agnostic, not strictly an atheist. While reading up on planning for this blog, I came across competing claims about who authored the Second Five-Year Plan and who established the Central Statistical Organisation. Knowing about the people, institutions and countries involved was necessary from different perspectives.

I decided to resolve the issue of authorship. It finally ended up like a whodunit. In the end, whatever I planned to write was a composite blog post covering, among other things, the life of PC Mahalanobis, the history of the Indian Statistical Institute, the story of Russian planning and Russian economists, antecedents of Indian planning and so on. One thing led to the other, and new things and perspectives started cropping up. I read much more than I might have done in my two years of postgraduate study. This explains the delay of more than three months. I am breaking up the post on IG’s tenure at the Ministry into three or four, or more.

The second reason I would have said no to moving to one of the research departments relates to a failed publication, where I was to publish a paper in collaboration with somebody, which never happened. This also has an ISI connection. In the next post, I will write about PC Mahalanobis and the Institute he created, which is necessary to understand some of the complex issues on authorship. In the post after that, I will write about the second five-year plan, including what I think of its authorship.

The link to the next post on Dr IG Patel is below:

You may also like to share or subscribe:

Thank you so much Sreekumar.

Its a fascinating read on your friendship with Ashish. We were also quite pally but nowhere the deep bond that both of you shared. Incidentally, Ashish joined in my place when I had been on transfer from the Kolkata Office to the Central Office in 2007.

Your piece was very lucid and sprinkled with deep empathy.

God bless you dear.

To read the piece on IGP as the DEA later.

Not only is the main article on IG worth your time but also the personal anecdote about an endearing friendship in the policy corridors of the country!

Thank you for this labour of love Sir! I do hope you will come out with a memoir soon!